|

|

Polaris Star Farm

Kaufman County, Texas

© 2012 - 2020

Kaufman County, Texas

© 2012 - 2020

Breeding to the Standard of Perfection

The Standard of Perfection (SOP) lists what the ideal specimen of a breed should be. This doesn't mean that every bird is going to look

EXACTLY like this - because they don't. But it provides the breeder with a blueprint of the characteristics that makes that bird look like a

particular breed, so they can try to keep a somewhat uniform appearance among birds in their flock and get as many of the best

characteristics in their birds as they can. You don't want your Java looking like some other chicken breed.

Utility production should also be a consideration in SOP breeding, despite the idea that SOP breeding is all about making "pretty birds". Productivity is mentioned in the SOP book but it seems sometimes people forget about it. Recently, APA officers have been looking at ways to get breeders to pay more attention to the utility purposes of a breed, in addition to the appearance. This will hopefully improve the situation for breeds that are at risk for extinction and get more people willing to raise standard-bred poultry.

The Standard of Perfection is copyrighted by the American Poultry Association (APA), so you will have to get the SOP for yourself in order to have all the detailed information you'll need about the Java. There are free copies and cheap copies of the SOP found online, however, these copies do not have the most current information in them. The Java SOP has not changed too drastically over the years, but there have been some changes, and there is up to date illustrations and some other essential information, on both Javas and more general poultry issues, in the newest version of the SOP. For breeding chickens seriously, you need a copy of the SOP.

Click here to go to http://www.amerpoultryassn.com/store.htm and get your copy of the SOP.

Utility production should also be a consideration in SOP breeding, despite the idea that SOP breeding is all about making "pretty birds". Productivity is mentioned in the SOP book but it seems sometimes people forget about it. Recently, APA officers have been looking at ways to get breeders to pay more attention to the utility purposes of a breed, in addition to the appearance. This will hopefully improve the situation for breeds that are at risk for extinction and get more people willing to raise standard-bred poultry.

The Standard of Perfection is copyrighted by the American Poultry Association (APA), so you will have to get the SOP for yourself in order to have all the detailed information you'll need about the Java. There are free copies and cheap copies of the SOP found online, however, these copies do not have the most current information in them. The Java SOP has not changed too drastically over the years, but there have been some changes, and there is up to date illustrations and some other essential information, on both Javas and more general poultry issues, in the newest version of the SOP. For breeding chickens seriously, you need a copy of the SOP.

Click here to go to http://www.amerpoultryassn.com/store.htm and get your copy of the SOP.

Why is SOP breeding useful?

Now that you've gotten a copy of the SOP and have an idea of what you're looking for in your birds, big things you need to focus on are vigor,

size, and type.

Unless you cross breed your birds, they will generally come out with the correct colors. There are some exceptions to this with Javas that we'll go over when we talk about feather color, but feather color is something that should be considered a little farther down the ladder of importance unless you have something really wrong with your Java's feather color.

Unless you cross breed your birds, they will generally come out with the correct colors. There are some exceptions to this with Javas that we'll go over when we talk about feather color, but feather color is something that should be considered a little farther down the ladder of importance unless you have something really wrong with your Java's feather color.

Vigor is the health and vitality in your chickens. Your chicken should have a good solid

skeletal frame and plenty of room inside for its internal organs to grow and to be able to

produce eggs and meat. You want birds that like to forage and rustle up some of their own

food. Look at their nails and see who has short nails from doing a lot of scratching and

digging.

Don't breed from sickly chickens. You want chickens that can not only survive, but thrive. You want chickens that are strong and fit and will pass on their vigor to their offspring. If you routinely have to help chicks get out of their shells, those chicks don't have good vigor. When you're looking at which birds to breed, try to choose birds that would be the survivor in a survival-of-the-fittest contest. Birds with good vigor will be less susceptible to diseases.

You'll want to think twice about breeding using a rooster than runs and hides when a hen looks at him sideways. You want your breeding male to be willing to fight another rooster for the rights to be "top cock" and mate with the hens. No, this does not mean you need to set up cock fights. But as you're hatching and raising your chicks, you should take note of which males are more dominant over the other males, particularly when they are

Don't breed from sickly chickens. You want chickens that can not only survive, but thrive. You want chickens that are strong and fit and will pass on their vigor to their offspring. If you routinely have to help chicks get out of their shells, those chicks don't have good vigor. When you're looking at which birds to breed, try to choose birds that would be the survivor in a survival-of-the-fittest contest. Birds with good vigor will be less susceptible to diseases.

You'll want to think twice about breeding using a rooster than runs and hides when a hen looks at him sideways. You want your breeding male to be willing to fight another rooster for the rights to be "top cock" and mate with the hens. No, this does not mean you need to set up cock fights. But as you're hatching and raising your chicks, you should take note of which males are more dominant over the other males, particularly when they are

Where To Start: Vigor, Size, and Type

Size seems pretty obvious. But it is possible to have a fluffy featherd bird that doesn't weigh as much as it should or it could weigh too much.

According to literary sources, Javas generally over the years have not been as large as the SOP calls for, so you will probably be working

toward increasing the size of your birds.

WEIGHT/SIZE

TYPE

When you are trying to determine which of your Javas have the best type, you need to spend some time observing them, in all kinds of poses

and movement, to determine if you see any specific flaws that are present ALL of the time. A still photograph can capture a flaw in one pose,

that is not really present in the bird, so make sure you are seeing your Javas in all kinds of different poses before making a final decision on

breeders. Ideally, you want photos from all angles, from above to see the width of their back and if they have pinched tails; from behind to see

their tail spread; from the front to see the width of their chest and their stance and legs; and a profile view to see their length of back and their

tail angle, as well as the brick shape and breast line.

***A good trick is to take digital photos of your chickens and then turn them to black and white. That way, your eye is not drawn to the feather color, or to colors in the background. This helps you to concentrate on your bird's overall body shape better.

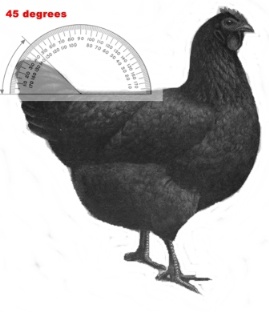

***Note about back and tail angle: If you have juveniles with the correct tail angle when they are less than a year old, they may have tails that are too high by the time they are over a year old. We see this more in our females but occasionally in the males too. If a pullet is flatter from neck to the tip of her tail feathers, she will usually have the correct tail angle once she is a year or two old. Not all Javas are like this, but it is something to watch out for as you raise Javas.

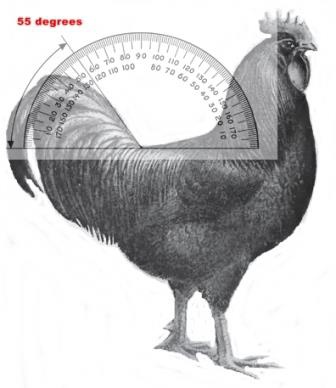

For showing purposes, you'll need to exhibit the birds which more closely resemble the SOP tail angle to exhibit no matter what their age. For breeding purposes, you'll need to look at the males/females to be mated, and try to choose birds that complement each other. If you breed a hen that had the correct tail angle as a juvenile, but whose tail angle got too high once she was a fully matured adult, you may find yourself with more offspring that have a tail angle too high when they are very young, so they won't meet the Standard for the type/tail angle at any age. In our flock, we see more females than males that have tails too high. If you have females with high tails, you may want to consider mating them them with males who have tails that are lower than 55 degrees to try to get the tail angle in both sexes back to where they should be. Remember - it's a balancing game when you're breeding, trying to offset flaws and complement good traits.

***A good trick is to take digital photos of your chickens and then turn them to black and white. That way, your eye is not drawn to the feather color, or to colors in the background. This helps you to concentrate on your bird's overall body shape better.

***Note about back and tail angle: If you have juveniles with the correct tail angle when they are less than a year old, they may have tails that are too high by the time they are over a year old. We see this more in our females but occasionally in the males too. If a pullet is flatter from neck to the tip of her tail feathers, she will usually have the correct tail angle once she is a year or two old. Not all Javas are like this, but it is something to watch out for as you raise Javas.

For showing purposes, you'll need to exhibit the birds which more closely resemble the SOP tail angle to exhibit no matter what their age. For breeding purposes, you'll need to look at the males/females to be mated, and try to choose birds that complement each other. If you breed a hen that had the correct tail angle as a juvenile, but whose tail angle got too high once she was a fully matured adult, you may find yourself with more offspring that have a tail angle too high when they are very young, so they won't meet the Standard for the type/tail angle at any age. In our flock, we see more females than males that have tails too high. If you have females with high tails, you may want to consider mating them them with males who have tails that are lower than 55 degrees to try to get the tail angle in both sexes back to where they should be. Remember - it's a balancing game when you're breeding, trying to offset flaws and complement good traits.

Type refers to the body type of the bird. Just as people have body types that are referred to as pear-shaped, apple-shaped, hour-glass, etc.,

chickens have a body type also. Body type (conformation) is a huge part of what makes a bird look like the breed it belongs to.

When you're looking at your Java's type, you'll have to determine your own interpretation of the SOP. The SOP does have some detailed descriptions of the breed characteristics, but there are also some parts that can be pretty subjective. Be aware - you may interpret the SOP one way, but get to a show and have a judge interpret it differently. So you'll have to do your best to breed to what interpretation you decide most closely matches the description of the SOP, since words like "large", "broad", "small", and "full" are subjective words and can leave a lot open to interpretation.

When you're looking at your Java's type, you'll have to determine your own interpretation of the SOP. The SOP does have some detailed descriptions of the breed characteristics, but there are also some parts that can be pretty subjective. Be aware - you may interpret the SOP one way, but get to a show and have a judge interpret it differently. So you'll have to do your best to breed to what interpretation you decide most closely matches the description of the SOP, since words like "large", "broad", "small", and "full" are subjective words and can leave a lot open to interpretation.

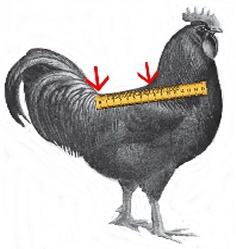

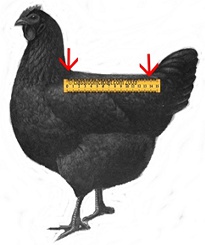

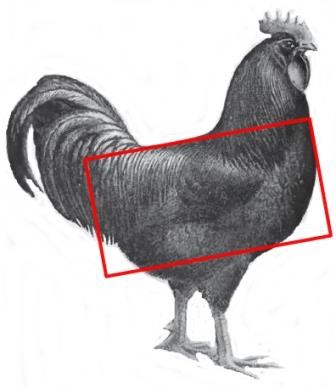

Javas bred to today's SOP should have long

backs. The length of the back is best viewed from

the side, and can be measured with a ruler from

the base of the neck to the base of the tail, to get

a more accurate idea of back length when you are

deciding on breeders or birds to show.

Photos can be deceiving when it comes to back length, depending on the bird's stance and whether or not the photo's size has been altered, so measuring the live bird will give you a better idea of their true back length, rather than relying entirely on eyeballing photos of your chickens.

Photos can be deceiving when it comes to back length, depending on the bird's stance and whether or not the photo's size has been altered, so measuring the live bird will give you a better idea of their true back length, rather than relying entirely on eyeballing photos of your chickens.

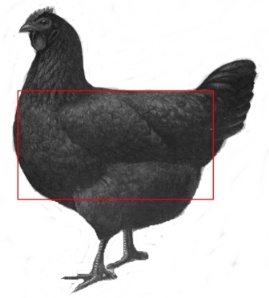

In addition to having a long back, the Java should have a wide back. The broadness of their backs are viewed better from above. This

broadness of back is also good for utility purposes for both meat and egg production. When you're comparing birds to choose breeders, if all

other things are equal between the birds, you'll want to choose the birds that have greater back length and width. Ideally the width should

extend all the way from front to back. Notice the body width differences in the photos below, with some looking wide all the way down their

body and others narrowing toward the back.

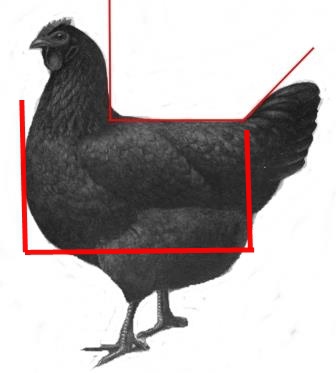

In the profile view, females should have more of a flat back from neck to tail while the males' back should angle/dip down a little, just before

the tail goes up. The tail angle is measured from a line horizontal to the ground, not horizontal to the chicken's back.

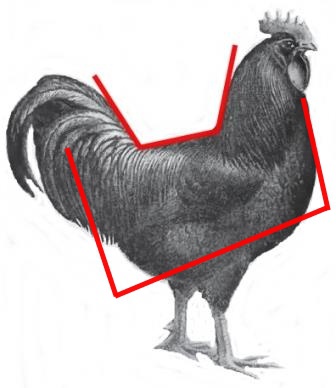

The overall Java body shape is somewhat of a rectangle or brick shape. The male Java has his brick shape at a slight angle, consistent with

his slightly more upright stance. The female's rectangular shape sits more horizontal than the male's.

When looking at body type, pay attention to the back and tail angle that is making up the top outline of the bird, and also look at the

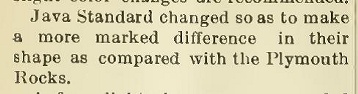

underline of the bird. Looking in your SOP book at Javas, as well as Plymouths Rocks, Rhode Island Reds, and Jersy Giants (breeds that

were made using Javas), can help you learn to recognize the subtle breed differences that you're looking for in your Javas.

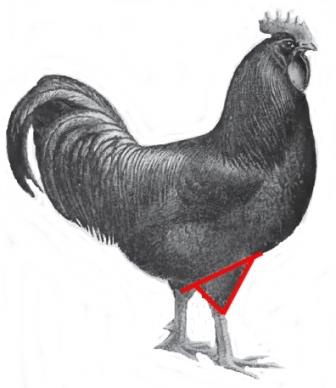

Although the SOP does not specifically mention it, it has been generally accepted that the males particularly, would ideally have somewhat

of a clear differentiation between the underline of their body and their legs. From what we have seen so far, being a little too fluffy underneath

so that the legs disappear into the fluff seems to be common in many Javas today.

As you're picking your breeders, you should be weighing them to see if they meet the correct

weight for a Java. Don't just eyeball them or pick them up and think "This chicken weighs about

what a gallon of milk weighs" - use a scale.

If you don't have a scale that your chicken can (or is willing to) stand on, then take the bathroom scale outside and either put the chicken in a cage or box to weigh it (subtracting the weight of the cage/box), or weigh yourself and then pick up the chicken you're examining, and weigh both of you. Then subract your weight to get the weight of the chicken you held. You can also buy a fish scale (fishing/camping section) and hang a cage from the fish scale and then put your bird in the cage. In case you're wondering, yes, we really do take a scale to the pasture to weigh our birds.

If you don't have a scale that your chicken can (or is willing to) stand on, then take the bathroom scale outside and either put the chicken in a cage or box to weigh it (subtracting the weight of the cage/box), or weigh yourself and then pick up the chicken you're examining, and weigh both of you. Then subract your weight to get the weight of the chicken you held. You can also buy a fish scale (fishing/camping section) and hang a cage from the fish scale and then put your bird in the cage. In case you're wondering, yes, we really do take a scale to the pasture to weigh our birds.

You'll see that there are weights for juveniles (pullets/cockerels) and weights for adult birds (hens/cocks). When a chicken turns a year

old, it is considered an adult (hen/cock). There is no hard and fast rule about what age a bird should reach the specified weight. However

if you exhibit the bird at a show, you'll want to make sure that you are within the weight guidelines no matter the exact age of your bird.

Heritage Javas don't mature as fast as today's more recently produced hybrid breeds, so you will probably see some continued growth

beyond the one year mark in your birds.

When you are choosing breeders, particularly when you are looking at juvenile birds and culling them at younger ages, weight is an important factor. The sooner your pullets and cockerels reach SOP weight, the sooner they can be ready to exhibit at shows or be butchered with more meat on them. This is a good reason to put ID of some kind on your birds when they are young - so you can make note of which birds are growing faster and becoming heavier at an earlier age. You can then take the information into account when you start culling your flock and determining who you will be using as breeding stock. Sometimes you will have a bird that is lightweight/undersized, but has other great characteristics - that's ok, you can beed with them, but try to match them to a mate that is the right size, and watch out for undersized birds in the offspring.

When you are choosing breeders, particularly when you are looking at juvenile birds and culling them at younger ages, weight is an important factor. The sooner your pullets and cockerels reach SOP weight, the sooner they can be ready to exhibit at shows or be butchered with more meat on them. This is a good reason to put ID of some kind on your birds when they are young - so you can make note of which birds are growing faster and becoming heavier at an earlier age. You can then take the information into account when you start culling your flock and determining who you will be using as breeding stock. Sometimes you will have a bird that is lightweight/undersized, but has other great characteristics - that's ok, you can beed with them, but try to match them to a mate that is the right size, and watch out for undersized birds in the offspring.

2-4 months old and beginning to have their hormones flowing. If your rooster doesn't care about whether or not there is another male

around the hens, that rooster may not be as fertile or may not be able to get the mating job accomplished with a fussy hen or when there

is another male around that tries to knock him off of a hen.

Good husbandry also plays a part in the "vigor" of a bird. If your birds look unhealthy or just not quite as good as they could look, but are not obviously ill, then you need to look at other factors that could be causing problems - like poor quality ingredients in their feed, pens full of ammonia fumes, pests like lice/mites, etc.. Sometimes thing change that we aren't aware of, and we have to change our husbandry of the chickens in order to keep them at their best.

Good husbandry also plays a part in the "vigor" of a bird. If your birds look unhealthy or just not quite as good as they could look, but are not obviously ill, then you need to look at other factors that could be causing problems - like poor quality ingredients in their feed, pens full of ammonia fumes, pests like lice/mites, etc.. Sometimes thing change that we aren't aware of, and we have to change our husbandry of the chickens in order to keep them at their best.

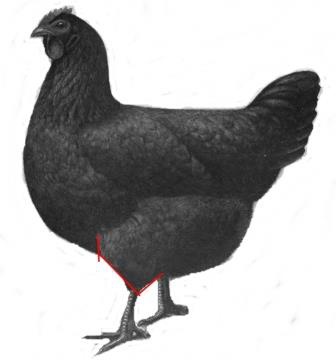

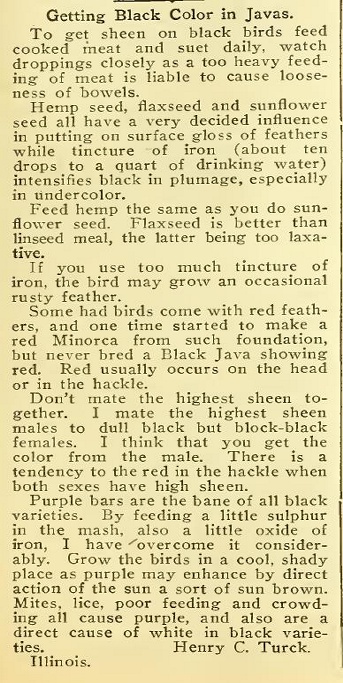

COMB

Javas are single combed chickens. The SOP calls for their combs to be "moderately small". Of course this is a description that is both

subjective and relative to other birds in your flock. You'll have to use your judgement as to what "moderately small" means, and it may not

mean the same to you as it does to someone else. In talking with other Java breeders, it seems that modern Javas, epecially males, tend

toward larger combs, particularly when they live in the hot South. The ideal Java will have 5 comb points.

There is mention in antique literature that the points on the Java's

comb should start above the eye, instead of lower on the comb

toward the beak. From what we have seen, there seems to be a

mix of Javas out there today that have comb points starting at

the eye, and others that start closer to the beak. Where the first

comb point starts is not an SOP requirement. It is a part of Java

history, and it does look nice when you are able to match up

what vintage literature says is a "proper Java comb", with the rest

of the Java SOP traits. However, where the first comb point starts

has no value other than perhaps aesthetic value, and whether or

not you try to breed to this particular comb trait is up to you. The

presence or absence of this trait should theoretically not count

against you in a show, and you shouldn't worry yourself silly

trying to get only Javas that have comb points that start far back

on the comb. From old photos & sketches we've seen, even

Javas 100+ years ago often did not have this "proper" Java comb.

Wright's Book of Poultry 1912

Combs are not the most important thing when it comes to Javas,so don't fret too much over them unless you have combs that are seriously

flawed. Side sprigs in combs, and combs that are flopped over, are two disqualifications that we have seen occur in Javas. You'll want to look

in your SOP for more comb DQs. Combs that squiggle into c-curves and s-curves seem to be fairly common in Javas. You want your Java's

comb to be as straight as possible.

Under ideal circumstances, you should never breed chickens with seriously flawed combs (or other serious flaws). However, there are times that you may choose to do so. If you have an outstanding chicken with a side sprig, you may choose to breed it, knowing that it will come up more often in the offspring. You'll have to be even more conscientious when choosing breeders from the offspring of a flawed comb parent, to make sure that you don't cement that flaw into your flock, but if the mating also brings in the best qualities of the bird with the flaw, then it can sometimes be worth it to work through the flaw.

We have a Java cock that had a side-sprig that didn't show up until he was two years old. When we first mated him, his side sprig had not shown up yet, but his offspring had side-sprigs show up before their first birthday. This is why if possible, it is nice to wait until your birds are a couple of years old before breeding them - so the birds are FULLY mature and less likely to have flaws show up after you've bred them.

Of course when you are needing to get more Javas on the ground as backups in case of losses, it isn't always feasible to wait until your birds are two years old before mating. Don't feel like you must wait two years before breeding a bird. Better to have birds with flaws to work out of the flock, than to keep so few birds that if you lose any, it sets you back years in your breeding program while you try to obtain more birds and bring them up to where you were with the previous generation.

Under ideal circumstances, you should never breed chickens with seriously flawed combs (or other serious flaws). However, there are times that you may choose to do so. If you have an outstanding chicken with a side sprig, you may choose to breed it, knowing that it will come up more often in the offspring. You'll have to be even more conscientious when choosing breeders from the offspring of a flawed comb parent, to make sure that you don't cement that flaw into your flock, but if the mating also brings in the best qualities of the bird with the flaw, then it can sometimes be worth it to work through the flaw.

We have a Java cock that had a side-sprig that didn't show up until he was two years old. When we first mated him, his side sprig had not shown up yet, but his offspring had side-sprigs show up before their first birthday. This is why if possible, it is nice to wait until your birds are a couple of years old before breeding them - so the birds are FULLY mature and less likely to have flaws show up after you've bred them.

Of course when you are needing to get more Javas on the ground as backups in case of losses, it isn't always feasible to wait until your birds are two years old before mating. Don't feel like you must wait two years before breeding a bird. Better to have birds with flaws to work out of the flock, than to keep so few birds that if you lose any, it sets you back years in your breeding program while you try to obtain more birds and bring them up to where you were with the previous generation.

Now that we've discussed *building the house*, we can talk about some of the accessories and paint job that further enhance your Java's

appearance.

COLORING

Javas come in two APA-recognized colors: Black and Mottled. As chicks, they have yellow and black fluff, with Black Java chicks having

more black fluff than the Mottleds. As they grow, they will have white and black feathering, with some Mottled youngsters looking more white

than black & white. As they get closer to maturity and grow new feathers, the black feathering should become more predominant, however

you will find variations in the amount of white and black in your Mottled birds, even among hatchmates.

Since the 1800s, there have been Javas with non-standard

coloring in them, red,"straw", or brassy colored feathers,

usually in the hackles and saddles.

There are two theories of thought on using these birds as breeders. One is that you should never breed a Java showing these incorrectly colored feathers because you will have to cull more birds later on since the red feathering will show up with more frequency if you breed them.

The other theory is that you must periodically breed a Java with red feathering back into the flock in order to maintain the metallic green sheened black feathering, otherwise you could wind up with birds with dull, matte black feathering.

We have not been breeding long enough to see if the metallic sheen can be lost in a flock and then regained if a red-feathered Java is bred into the bloodline, so we can't speak to whether this old theory actually works or not.

In our flock of both Black and Mottled Javas, which include different bloodlines in the Mottleds, we have seen both red feathering and gold feathering occurring, as mentioned in old literature. So far, we are only seeing it occur in males, but have noted that there is some difference in coloration of the female offspring from these males. Currently we have a color project going on, to see what happens with the subsequent generations of offspring from these non-standard colored Javas, however we don't use these birds with non-standard colored feathers for the normal SOP breeding lines. We have found in the color project birds, that the birds with red and gold feathering tend to have pink feet, and they pass the pink foot trait to most of their offspring. Since both Black and Mottled Javas need to have yellow on the soles of their feet, using these red and gold feathered Javas would cause further foot color problems in a Standard-bred flock.

These nonstandard colored birds do not always breed true to their nonstandard coloring and it is even more difficult to get the females to show the nonstandard red and gold coloring. The red coloring in one flock of Black Javas has been worked on for roughly 7 or 8 years by one breeder, to make a modern "Auburn" Java, however they are still a work in progress and are not recognized by the APA.

There are two theories of thought on using these birds as breeders. One is that you should never breed a Java showing these incorrectly colored feathers because you will have to cull more birds later on since the red feathering will show up with more frequency if you breed them.

The other theory is that you must periodically breed a Java with red feathering back into the flock in order to maintain the metallic green sheened black feathering, otherwise you could wind up with birds with dull, matte black feathering.

We have not been breeding long enough to see if the metallic sheen can be lost in a flock and then regained if a red-feathered Java is bred into the bloodline, so we can't speak to whether this old theory actually works or not.

In our flock of both Black and Mottled Javas, which include different bloodlines in the Mottleds, we have seen both red feathering and gold feathering occurring, as mentioned in old literature. So far, we are only seeing it occur in males, but have noted that there is some difference in coloration of the female offspring from these males. Currently we have a color project going on, to see what happens with the subsequent generations of offspring from these non-standard colored Javas, however we don't use these birds with non-standard colored feathers for the normal SOP breeding lines. We have found in the color project birds, that the birds with red and gold feathering tend to have pink feet, and they pass the pink foot trait to most of their offspring. Since both Black and Mottled Javas need to have yellow on the soles of their feet, using these red and gold feathered Javas would cause further foot color problems in a Standard-bred flock.

These nonstandard colored birds do not always breed true to their nonstandard coloring and it is even more difficult to get the females to show the nonstandard red and gold coloring. The red coloring in one flock of Black Javas has been worked on for roughly 7 or 8 years by one breeder, to make a modern "Auburn" Java, however they are still a work in progress and are not recognized by the APA.

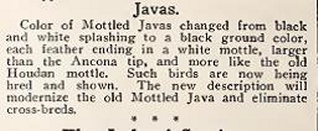

If you look closely at Mottled Javas, most of them have more of a splash

appearance. They have been this way since the 1800s, but apparently the

term "Mottled" sounded better than "Splashed Java" when they were

naming them. In the early 20th century, a change was made to the SOP to

require a more definitive type of mottling to the feathers, requiring the white

tips to have a v-shape at the end of the black feathers, and a certain

number of white tipped feathers per section of black feathers. This change

in the SOP regarding the mottling, was made because some Mottled Javas

had been bred and shown with this more precise mottling pattern, and it

seems that they were trying to make the Java apear more modern -

perhaps in an attempt to get more folks interested in breeding them. At this

point, looking at the historical Java information, I am under the impression

that while a few Javas may have had this new precise mottling pattern,

most did not, and likely some politics was involved in getting the SOP

changed. Regardless of how or why the SOP was changed, we have the

current standard of precise mottling to work toward. As far as we know,

because so few Javas are exhibited at shows, Javas are not getting heavily

penalized for having the more common splash appearance versus the

v-shaped mottling. Of course if there were a lot of Mottled Java competition

at a show, having the more precise v-shaped mottling would likely be an

advantage over the splashed-look Mottled Javas.

Mottled Javas will get whiter as they age. When breeding them, you will want to look at mating birds that complement each other's good traits and offset their faults - in this case using a bird with LESS white on it and mating it with a bird that has TOO MUCH white on it. It is very common for Mottled Javas to have some all-white wing and tail feathers. It is also somewhat difficult to get rid of this trait, so when you find Mottled Javas in your flock that do not have solid white wing/tail feathers, you'll want to consider them for breeders if their other traits are good and/or you have a bird to mate with them that can help offset their faults. The white color in the Mottleds also often extends to the fluff, and you will find Mottleds with a lighter gray or even white fluff instead of the slate-colored fluff the SOP calls for.

For showing purposes, juvenile Mottled Javas that closely match the SOP in the amount of mottling, may have too much white on them by the time they are adults, so your show quality pullets and cockerels may not be the adult birds you breed with, like the case with tail angles that can change as your Javas mature.

Mottled Javas will get whiter as they age. When breeding them, you will want to look at mating birds that complement each other's good traits and offset their faults - in this case using a bird with LESS white on it and mating it with a bird that has TOO MUCH white on it. It is very common for Mottled Javas to have some all-white wing and tail feathers. It is also somewhat difficult to get rid of this trait, so when you find Mottled Javas in your flock that do not have solid white wing/tail feathers, you'll want to consider them for breeders if their other traits are good and/or you have a bird to mate with them that can help offset their faults. The white color in the Mottleds also often extends to the fluff, and you will find Mottleds with a lighter gray or even white fluff instead of the slate-colored fluff the SOP calls for.

For showing purposes, juvenile Mottled Javas that closely match the SOP in the amount of mottling, may have too much white on them by the time they are adults, so your show quality pullets and cockerels may not be the adult birds you breed with, like the case with tail angles that can change as your Javas mature.

American Poultry Journal 1922

It does happen on occasion that a Black Java will wind up with a few stray white spots in their feathers as adults. White spots in a Black Java

will disqualify them at a show. Try not to breed Black Javas that have white in their feathers if you can help it.

White feathered "sports" have also occurred in Javas, with the birds maturing into all white feathers. White Javas have not been recognized by the APA for more than 100 years and are even more rare than Black and Mottled Javas.

White feathered "sports" have also occurred in Javas, with the birds maturing into all white feathers. White Javas have not been recognized by the APA for more than 100 years and are even more rare than Black and Mottled Javas.

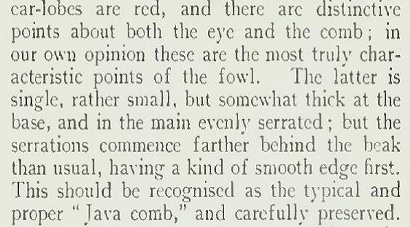

Both the Black and the Mottled Java should have a green metallic sheen to

their black feathers. A purple sheen, sometimes seen in the form of bars,

other times seen as just a purple cast to the feathers, can be a problem in

black feathered birds. There are various theories out there as to the cause.

It is felt that it can be genetic, in which case not breeding birds with a

purple sheen/barring should help. In other cases, it is felt that environmental

factors play a part, such as amount of sunlight, stress, or feeding too

much milo to a bird. Should you find yourself with a Java that has a purple

sheen or barring to it, you'll have to investigate, determine what you believe

is the cause, and take measures to fix the problem.

At right is a short article by an early 20th century Java breeder with his tips

for obtaining a good black color in Javas. We don't have firsthand

experience with using these old tips, but it's something to consider if you

ever have problems with the black coloring of your flock.

American Poultry Journal 1921

LEGS

As you're breeding, remember that Javas are LARGE fowl. Being dual purpose chickens, they have large skeletal frames to hold more meat

than what you'll find on an egg laying breed. Leg size should be a factor for consideration when you're choosing breeders. Antique poultry

literature has mentions of some Javas being too fine-boned. Ideally, Javas should have larger, thick legs to support their weight - preventing

injuries when landing from roosts or when flying (yes, even adult Javas can fly short distances given enough space and incentive).

Large legs means you'll likely have to order leg bands online as most legbands we see at the feed store are too small for Javas. For some purposes, we use colored spiral ring leg bands. For the majority of our birds, the cocks need at least a size 14, if not a 16 mm band, and hens usually need a 14 mm band with some finer-boned hens using a 12 mm band.

It is unlikely you will find Javas listed on a size-recommendation chart for leg bands. They do usually list Plymouth Rocks, which should be of a similar size to Javas, but so far all of the size charts we've seen recommend a size 11 band for hens and a size 12 band for cocks. Perhaps hatchery stock birds might fit these sizes, but for our Javas, those sizes rarely fit our full-grown Javas.

Large legs means you'll likely have to order leg bands online as most legbands we see at the feed store are too small for Javas. For some purposes, we use colored spiral ring leg bands. For the majority of our birds, the cocks need at least a size 14, if not a 16 mm band, and hens usually need a 14 mm band with some finer-boned hens using a 12 mm band.

It is unlikely you will find Javas listed on a size-recommendation chart for leg bands. They do usually list Plymouth Rocks, which should be of a similar size to Javas, but so far all of the size charts we've seen recommend a size 11 band for hens and a size 12 band for cocks. Perhaps hatchery stock birds might fit these sizes, but for our Javas, those sizes rarely fit our full-grown Javas.

The short reason is because you want your Java to look like a Java.

Sometimes people who aren't interested in exhibiting their birds at a poultry show think that breeding to the SOP is useless, because they can hatch eggs from their birds and still wind up with the same feather color as the parents and they think the birds look the same. Our eyes are automatically drawn to color, so to the untrained poultry breeding eye, all that person sees is a general chicken shape and the color of a chicken.

But so much more goes into a breed of poultry than just what their feather color is. Things like body type, tail angle, carriage, comb size, topline and underline - these things and more, all go into making a bird a particular breed. There are some breeds that have similar feather coloring, and without the differences in certain physical characteristics, they could wind up looking alike.

Sometimes people who aren't interested in exhibiting their birds at a poultry show think that breeding to the SOP is useless, because they can hatch eggs from their birds and still wind up with the same feather color as the parents and they think the birds look the same. Our eyes are automatically drawn to color, so to the untrained poultry breeding eye, all that person sees is a general chicken shape and the color of a chicken.

But so much more goes into a breed of poultry than just what their feather color is. Things like body type, tail angle, carriage, comb size, topline and underline - these things and more, all go into making a bird a particular breed. There are some breeds that have similar feather coloring, and without the differences in certain physical characteristics, they could wind up looking alike.

American Poultry Journal 1897

Information on breeding black, white, and black & white birds from

Laws Governing the Breeding of Standard Fowl by W.H. Card 1912

Black Java cock that molted into nonstandard

metallic gold feathering (this is gold, not silver)

Mottled Java cock that molted into an adult with

nonstandard black and metallic gold feathering

Mottled Java cockerel showing nonstandard

red feathering

Black Java cock that molted into adult with nonstandard red

feathers.

Information on breeding red birds from Laws Governing

the Breeding of Standard Fowl by W.H. Card 1912

LEG & FOOT COLOR

The SOP calls for both Black and Mottled Javas to have the

bottoms of their feet be yellow. The shanks and toes of the Black

Java should preferably be black, but may be willow colored (dusky

yellowish green). The shanks and toes of the Mottled Java should

be a broken leaden-blue and yellow coloring.

As mentioned already, pink feet (varying in shade from a pale pink to a caucasian peachish color to a whitish color), are found in Javas. This color however will disqualify a Java from a show. This is one of those areas where you do not want to breed these birds unless you have no other good choices, since incorrect foot color is an absolute DQ in a show bird, and the more you breed birds with a DQ flaw, the more the trait pops up in the bloodline.

We've found that most of our Black Javas have kept their black leg and toe color as they mature, although some people have let us know they've had a fading out of their Blacks' leg color also. Our Mottled Javas all tend to have their leg color wash out as they mature. In some of them, this occurs when they reach sexual maturity, in others it happens closer to the time they are a year old. Because the Mottled Javas have a dark gray-ish blue and yellow colored leg, their legs tend to wash out to a gray color. Even the yellow color in the soles of their feet can wash out and look grayish.

As mentioned already, pink feet (varying in shade from a pale pink to a caucasian peachish color to a whitish color), are found in Javas. This color however will disqualify a Java from a show. This is one of those areas where you do not want to breed these birds unless you have no other good choices, since incorrect foot color is an absolute DQ in a show bird, and the more you breed birds with a DQ flaw, the more the trait pops up in the bloodline.

We've found that most of our Black Javas have kept their black leg and toe color as they mature, although some people have let us know they've had a fading out of their Blacks' leg color also. Our Mottled Javas all tend to have their leg color wash out as they mature. In some of them, this occurs when they reach sexual maturity, in others it happens closer to the time they are a year old. Because the Mottled Javas have a dark gray-ish blue and yellow colored leg, their legs tend to wash out to a gray color. Even the yellow color in the soles of their feet can wash out and look grayish.

As a general rule in chickens, loss of yellow pigmentation is a result

of being productive egg layers, as the females will deposit the yellow

pigment into the egg yolk instead of into their body tissues. However

we also see the leg color fading out in sexually mature Java males

as well.

You'll want to note each bird's leg and foot color early as chicks, and continue to monitor the color as they mature. If they do not have yellow soles of the feet once they are feathering out, it is unlikely they will grow into a yellow sole. You may find varying intensity of the yellow foot color amoung bids in the same hatch - make note of who has the best and brightest yellow coloring since by the time you choose your final breeders, most likely their yellow color will have already faded since they will have been at their sexual maturity level for a good while.

When males, and some females, reach sexual maturity, you'll likely see their legs redden. Sometimes the appearance is an overall red or dark pink color wherever they usually have yellow showing, other times you may see a line of red colored dots marching up their legs and along their toes. In our Blacks, we tend to see more redness in the toe webbing of the mature birds, while the Mottleds often show red all the way up the leg.

There are various sources out there that recommend feeding corn or marigold petals or dandelion flowers to chickens to help them get the extra yellow color back into their legs and feet. You may find chicken feed that has marigolds in it as a way to help make pretty egg yolks, but it usually isn't enough to help replenish the yellow coloring in the legs. We have used whole corn in winter time as an extra treat on the coldest days, and found that it can improve the yellow coloring in the feet and legs after a few weeks. In our experience, cracked corn in scratch grains did not provide the same results as feeding whole corn kernels.

You'll want to note each bird's leg and foot color early as chicks, and continue to monitor the color as they mature. If they do not have yellow soles of the feet once they are feathering out, it is unlikely they will grow into a yellow sole. You may find varying intensity of the yellow foot color amoung bids in the same hatch - make note of who has the best and brightest yellow coloring since by the time you choose your final breeders, most likely their yellow color will have already faded since they will have been at their sexual maturity level for a good while.

When males, and some females, reach sexual maturity, you'll likely see their legs redden. Sometimes the appearance is an overall red or dark pink color wherever they usually have yellow showing, other times you may see a line of red colored dots marching up their legs and along their toes. In our Blacks, we tend to see more redness in the toe webbing of the mature birds, while the Mottleds often show red all the way up the leg.

There are various sources out there that recommend feeding corn or marigold petals or dandelion flowers to chickens to help them get the extra yellow color back into their legs and feet. You may find chicken feed that has marigolds in it as a way to help make pretty egg yolks, but it usually isn't enough to help replenish the yellow coloring in the legs. We have used whole corn in winter time as an extra treat on the coldest days, and found that it can improve the yellow coloring in the feet and legs after a few weeks. In our experience, cracked corn in scratch grains did not provide the same results as feeding whole corn kernels.

Mottled Java cockerels, on right is the broken leaden-blue and

yellow of a slower maturing male. On the left is a sexually

mature cockerel showing the change of his leg color and now

has a reddened appearance where it had been yellow. This

reddened coloring is different from the pink feet that can be found

in Javas, which is a DQ. If the rooster had yellow feet before it

was sexually mature, it is generally safe to breed them and still

get the correct yellow-footed offspring.

Yellow feet on Mottled Java pullets. The amount of dark and yellow

coloring up the leg varies between individual birds.

Pink foot on a pullet. This Mottled pullet was hatched from our color

project birds, mother was Mottled, father was a black & metallic

gold feathered cock. Pink footed birds are most likely carrying the

genes of the nonstandard coloring, even if their feathers appear the

correct color, so if you breed them, you can wind up with more

offspring that have incorrect feather color and foot color.

EYE COLOR

Mottled Javas should have eyes that are reddish brown. Black Javas should have dark brown eyes that almost appear black. If your Black

Java's eye is not dark brown, chances are it has either the genes for mottling or red or gold feathering. We are seeing some orange colored

eyes in the Mottleds that turn up with red feathers in their plumage.

VIGOR

MATING JAVAS OF DIFFERENT COLORS

People frequently ask what happens when you mate Javas that are not the same color. Most folks that remember their elementary school

science classes know about Mendel's theories of genetics and the different percentages of pea plants that will have different characteristics.

Unfortunately, chicken genetics is more complicated. Even when you breed the same colors of Javas together does not mean that you're

guaranteed to come out with the exact proportions of different colored chicks with all the correct eye, feather, and leg color. There are just too

many variables in the DNA and genes that are recessive and don't show up in the birds until just the right combination of genes mix together.

This makes trying to determine the exact percentage of different colored offspring difficult, if not impossible, despite the online chicken

genetics calculator that many people are fond of playing with as they contemplate breeding a new color of chicken.

If you are breeding to the SOP for Black Javas, you will do best to stick with breeding only Black Javas together. If you breed another color of Java to a Black Java, you will introduce genes for incorrect feather and eye color and wind up with an increased problem of Black Javas that don't meet the SOP.

If you want to breed SOP Black Javas and don't have the best specimens, we recommend you get new stock rather than try to improve Black Javas by mating them to Javas of another color.

If you are breeding Mottled Javas, the addition of the Black Java into the mix is not generally as much a problem unless your Black Javas tend towards having pink feet. As we already noted, we have seen more problems with pink feet in our Black flock than in our Mottled flock. If there is any pink feet genes in your Black Java's makeup, you could inadvertently get the pink gene started in your Mottled flock (if you didn't already see it on occasion), even if the Black Java you use for mating does not exhibit pink feet.

What breeding a Black Java into your Mottle flock can help with, is to help decrease the amount of white in the feathers, if you are seeing birds that have excessive white at a young age. You may end up with some offspring that have eyes that are not the correct SOP coloring - we've seen some that have a mix of dark brown and red - so you'll need to cull for incorrect eye color and incorrect foot color in the offspring, just as you would if those incorrect colors came up any other time.

If you're breeding to the SOP, it is generally safer to breed a Black Java into a Mottled flock, than it is to breed a Mottled Java into a Black flock.

If you are breeding to the SOP for Black Javas, you will do best to stick with breeding only Black Javas together. If you breed another color of Java to a Black Java, you will introduce genes for incorrect feather and eye color and wind up with an increased problem of Black Javas that don't meet the SOP.

If you want to breed SOP Black Javas and don't have the best specimens, we recommend you get new stock rather than try to improve Black Javas by mating them to Javas of another color.

If you are breeding Mottled Javas, the addition of the Black Java into the mix is not generally as much a problem unless your Black Javas tend towards having pink feet. As we already noted, we have seen more problems with pink feet in our Black flock than in our Mottled flock. If there is any pink feet genes in your Black Java's makeup, you could inadvertently get the pink gene started in your Mottled flock (if you didn't already see it on occasion), even if the Black Java you use for mating does not exhibit pink feet.

What breeding a Black Java into your Mottle flock can help with, is to help decrease the amount of white in the feathers, if you are seeing birds that have excessive white at a young age. You may end up with some offspring that have eyes that are not the correct SOP coloring - we've seen some that have a mix of dark brown and red - so you'll need to cull for incorrect eye color and incorrect foot color in the offspring, just as you would if those incorrect colors came up any other time.

If you're breeding to the SOP, it is generally safer to breed a Black Java into a Mottled flock, than it is to breed a Mottled Java into a Black flock.

*White Javas

White Javas were recognized by the APA for only a

decade during the late 1800s. All varieties of Javas should

look the same except for the differences in their coloring.

The SOP for White Javas called for white feathers, bay eyes, and willow colored legs with yellow on the soles of their feet.

If you are going to breed White Javas, you'll have to decide which direction to take them in. The changes made to the Java SOP over the years have not been drastic, but today's Java does have a bit of a different look than the Java of the 1800s.

Because there is not a currently recognized SOP for a White Java, you'll have to decide if you want to follow the 1888 White Java SOP as your breeding guideline, or if you would rather use today's Java SOP for the non color related traits, putting the White Java feather/eye/leg color guidelines onto the more modern body style of the birds.

Or, you could choose to breed White Javas that have yellow legs, which are still historically accurate, though were not recognized by the APA.

The SOP for White Javas called for white feathers, bay eyes, and willow colored legs with yellow on the soles of their feet.

If you are going to breed White Javas, you'll have to decide which direction to take them in. The changes made to the Java SOP over the years have not been drastic, but today's Java does have a bit of a different look than the Java of the 1800s.

Because there is not a currently recognized SOP for a White Java, you'll have to decide if you want to follow the 1888 White Java SOP as your breeding guideline, or if you would rather use today's Java SOP for the non color related traits, putting the White Java feather/eye/leg color guidelines onto the more modern body style of the birds.

Or, you could choose to breed White Javas that have yellow legs, which are still historically accurate, though were not recognized by the APA.

The American Breeds of Poultry

Frank L. Platt

1921

Frank L. Platt

1921